|

|

Wong Jing

"The most important day for me is not the first day of shooting, it is the opening day. If the audience likes the movie, then I have done my job...to me a director is like a chef. I make the dishes that the audience wants to eat. Most directors love their movies, but I never fall in love with mine. When they are editing, it�s like they are making love to the film. They hate to finish it. But I don�t. I always edit my movies very fast. I try to give the audience what they want. That�s the way I�ve done it for the last 20 years."

One of Hong Kong's most prolific and controversial filmmakers, Wong Jing (sometimes credited as Wong Ching or Wang Jing) was born in 1956 in Hong Kong and got his start in the entertainment industry early, since his father Wong Tin Lam was a TV drama director. It seemed inevitable that he would follow in his father's footsteps, but first Wong attended the Chinese University of Hong Kong, majoring in Chinese Literature.

Wong didn't like college and skipped class a lot; some of his professors said they never saw him at all during the four years it took to earn his degree. In classic Wong style, he later said that the degree was worthless to him. Wong believed that he learned more about making movies and (perhaps more importantly) making money by cutting classes and hanging around studios, where he would get work as a director's assistant (basically a glorified errand boy) and writing scripts for his father's shows.

Long a devout fan of classic Cantonese cinema, Wong impressed many of the old-timers around the studios with his knowledge of movie trivia. Combined with his high work ethic and the abitlity to change scipts on the fly (a necessary skill in the fast-paced world of Hong Kong's entertainment industry), Wong had found his niche. By 1978 he made his entrance into the world of movies with his script Cunning Tendency, and in 1981, he had directed his first movie Challenge of the Gamesters.

Throughout the 1980's, Wong was one of Hong Kong's most prolific and bankable writers and directors. While most of his movies had little of the prestige of the "event" films done by people like Tsui Hark or John Woo, Wong had come upon a formula which virtually guaranteed to make the movie break even at the box office, which in the fast-paced world of Hong Kong films (where the average theatre run for a new movie is two weeks), is most times as good as it gets.

Wong's formula was simple: give the audience what it wanted, mostly in the form of high doses of sex, violence and toilet humor. Wong had always viewed writing and directing as a way to get into what he considered to be the real power job in Hong Kong movie making -- producing -- and by 1989, he had completed that task with Crocodile Hunter. Wong also formed his own production company, Wong Jing's Workshop Ltd., and later became a partner in the successful BoB (Best of the Best) company, along with director/screenwriters Andrew Lau and Manfred Wong.

As he would most likely admit, most of Wong's work is highly derivative of other films. Some of the most notorious examples of this include a couple of films seemingly taken straight from the hands of John Woo -- Return to a Better Tomorrow (1994) and The Last Blood: 12 Hours to Die (1990), which was renamed Hard-Boiled 2 in some markets. But some of Wong's "homages" are a bit more subtle, at least when compared to his usual blitzkrieg style.

For example, 1995's High Risk's Chinese name is one syllable away from the Chinese name for Die Hard, and similarly to the Willis film, much of it takes place in an office building where the hero (in this case Jet Li) must take on a group of robbers posing as terrorists to throw off the police. Even though his methods are sometimes condsidered "low-class", Wong has turned some of these "ripoffs" into highly successful films (both financially and artistically) in their own right. High Risk (re-named to Meltdown for its' US video release) did well at the box office and remains a favorite among fans around the world.

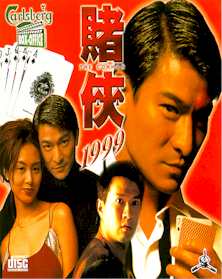

After working on King of Gamblers (1980) and Return of King of Gamblers (1981) with his father, Wong saw that there was a large audience for gambling films, of which he had been a fan of himself, dating back to the 1960's. He helmed the 1989 film Casino Raiders and then cemented the "modern gambling movie" later that same year with God of Gamblers, which was number one at the Hong Kong box office, beating out John Woo's gangster epic The Killer. God of Gamblers was so popular that its' sequels and spinoffs still continue on to this day. 1999's Conman in Vegas was the first movie ever to film directly inside the famous Caesar's Palace casino in Las Vegas, and Wong continues to use the formula to this day, with movies like The Conman 2002.

After God of Gamblers was parodied by All for the Winner (aka Saint of Gamblers, 1990), Wong -- as per his style -- adapted the series into containing more comedy, going so far as to use All for the Winner's star Stephen Chow in God of Gamblers II (1990). David Bordwell in his book Planet Hong Kong perhaps said it best: "Wong Jing hit upon his most successful formula; fittingly, Wong Jing may have swiped the Wong Jing style himself." Wong has said that these gambling movies -- specifically the "duels" at the end -- are his favorite to make.

Later, Wong again updated a popular genre, this time the "heroic bloodshed" crime movies of the 1980's personified by the work of directors such as John Woo and Ringo Lam, and helped define another genre -- "Triad Boys" -- with the film Young and Dangerous (1995) which came out through his company and was directed by one of his protoges, Andrew Lau.

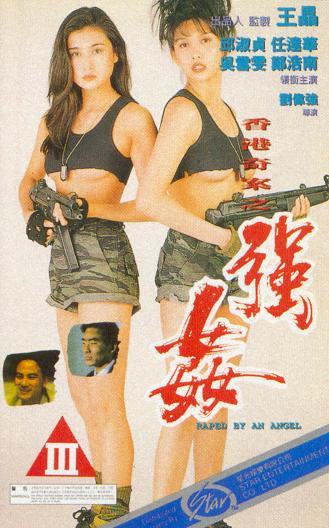

However, the genre (if a Hong Kong filmmaker could be held to a single one) Wong is most famous for was bludgeoned across many viewer's retinas with 1992's exploitation classic Naked Killer. A twist on the popular assassin genre, Naked Killer gave audiences the ultra-violence they had grown accustomed to in such films, but then upped the meter with a high dose of sex. The movie was very successful (especially with Western fans) and it ushered in a wave of Category III (the Hong Kong equivalent of the NC-17 rating) "femme fatale" films, most of which were produced, directed or written by Wong himself.

While his credits have been impressive by most standards, Wong has faced criticism from both fellow filmmakers and Hong Kong's notoriously picky critics. Wong had 32 director, 28 producer and 23 writer credits between 1990 and 1996. The "Steven Spielberg of Hong Kong" Tsui Hark lamented that these films were "cheap, fast, but no good" -- which, frankly, most of them were. However, it should be noted that these films were helping to keep the Hong Kong film industry alive in the face of a growing deluge of films from America, which were gaining in popularity in the East.

By 1993, after Jurassic Park took the number one spot at the local box office for the year and signaled the end of the "golden age" of Hong Kong movies, Hollywood's films had taken a firm hold in Hong Kong. It is due to filmmakers such as Wong that the industry is still alive today, especially after the departure of high-profile people like John Woo. In the mid to late 1990's, Wong's movies accounted for as much as thirty percent of the total box office take in Hong Kong. After experiencing a slump in 1995, Wong went so far as to appeal publicly to top stars to reduce their salaries (which would often cost as much as the film itself) so that Hong Kong movies could better compete with Western films.

Though most Hong Kong film companies play down promotion due to low budgets, Wong has become quite adept at it. For instance, for Chow Yun Fat's return to the God of Gamblers series with God of Gamblers Returns (1994), the trailer featured only one shot of the star. While filming 1993's City Hunter (itself a hot licensed anime product from Japan), Wong used the rights for the popular Street Fighter video game as well and combined them into one of the most inventive fight scenes in Chan's career. The Storm Riders (1998) was one of Hong Kong's biggest hits ever, thanks in no small part to Wong's clever promotional tie-ins for the movie. It is due to his business savvy that Wong is one of the few HK producers left that can still presell his movies to other Asian territories.

In response to comments leveled by critics about the validity of his movies, Wong has said in print that "I don't make films to please critics, I want the audience to be happy and for Hong Kong films to make money." Wong has chosen another medium -- his movies -- to deliver shots to other filmmakers; Last Hero in China (1993) is a parody of Tsui Hark's Once Upon a Time in China series, Boys Are Easy (1993) pokes fun at John Woo's macho male bonding with a sequence that parodies A Better Tomorrow, and the films Whatever You Want (1994) and Those Were the Days (1998) feature a character named "Wong Jing-Wai," a jab at art-house favorite War Kar-Wai.

Perhaps Wong's biggest salvo was High Risk, which operates under the guise of an action movie, but really amounts to an attack on Jackie Chan, who had tried to get him kicked off the set of City Hunter after the two got into shouting matches on the set. For those that do not know the history of the movie, the character Chan plays in the movie is a womanizer, and he wanted to play that down to save his "family" image, much to Wong's dismay. Chan also took offense to a sequence that had him learning moves from Bruce Lee via a screening of Game of Death. In High Risk, Wong goes so far as to include caricatures of Chan's father and manager, his supposed lack of business sense, and a rather graphic joke about the size of his penis in the film.

However, Wong has also used his films to deflate his own image. In Whatever You Want, one of the characters brags that she watched eight videos in a night, but then admits that they were Wong Jing movies, so she fast-forwarded through them all. Also, in Those Were the Days, Wong puts himself into the film as a geeky, overweight little boy.

Perhaps no discussion of a Hong Kong star or director is complete without mention of the "fluff" (news items) which surround their lives. Most every major player has at least a few stories (founded or unfounded) circulating about them, and Wong is no exception. He has long been a favorite of the notoriously rabid Hong Kong tabloid press for his relationships with female stars.

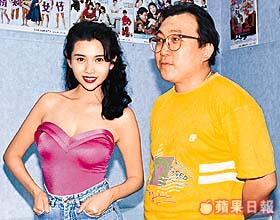

The most famous one occurred while Wong was still married, when he began dating Chingmy Yau, star of Naked Killer; the film had turned Yau from the romantic "girl next door" into the "man-eater" her fans have come to know and love. At this point, Wong seemingly became protective of his new girlfriend, but in an odd way.

Despite Yau's erotic roles, Wong maintained tight controls on the movies she starred in and refused to let her be shown fully nude (the most blatant example of this is a striptease sequence from 1994's Raped by an Angel). Strangely (given his protective nature of Yau), Wong would write in small roles for himself in many of Yau's movies, such as Deadly Dream Woman (1992), where he appears briefly as a sleazy "hostess" (escort/prostitute) club owner who wants to get into Yau's pants.

The pair eventually broke up, to much fanfare in the Hong Kong press. Yau later married a fashion designer and has now retired, but the rumors of other liasions continue to pop up. Other Hong Kong actresses Wong is reported to have relationships with include Loletta Lee and Ellen Chan, who later blasted Wong and his alleged "casting couch" during interviews.

Another long-running tabloid staple about Wong is his connection with the Triads (Hong Kong gangsters). In 1992, Wong had most of his teeth knocked out (and ended up having to use a wheelchair for a while) from a beating by a group of Triads. Apparently, he had said the wrong thing publicly about an actress, who happened to be going out with one of the local "Big Brothers" (head of a crime "family").

On the other side of the coin, it has been rumored that Wong has worked with the Triads, who have a large stake in the Hong Kong film industry. Many people say the only reason Jet Li and Stephen Chow (two of the most popular and highest-paid stars in Hong Kong) worked with Wong is because of a little "friendly persuasion" from the Triads. The Triad connection seems to continue to this day, as Wong often works with Wins Entertainment Group, a production company founded by the sons of a high-level Triad, Charles and Jimmy Heung.

Getting back to actual filmmaking, when he finds the time to actually direct a movie nowadays (he works on many as five films at a time in some way), Wong's filming methods are still considered unorthodox, even by Hong Kong standards. He often will totally ignore the action or fight scenes, trusting them to the second-unit (aka action) director. It has even been reported that Wong will listen to simulcasts of horse races (which, along with video games, is one of his non-film passions) or take a nap rather than film an action scene. While he has been criticized for his approach, it has allowed his action directors (such as Yuen Woo-Ping or Corey Yuen) great freedom in constructing their scenes, which often results in some of the most unique sequences put to celluloid.

Even though he is sometimes regarded as a hack or pornographer by his peers or critics, one of the most telling quotes about Wong -- and why his films have such widespread appeal -- comes from one of the characters in Whatever You Want: "Vulgarity is the basic instinct of human beings. Humans misinterpret vulgarity. I change vulgarity into art as to let you enjoy it."

(Thanks to Grady Hendrix, Simon Booth, Sebastian Tse, Wolverine's Hong Kong Film News and the books Planet Hong Kong, City on Fire and Asian Pop Cinema for their help with this section).